We received the first question for this blog! Here goes:

My question is, in Anarchy, how are large and small scale decisions made? How are significant disagreements adjudicated? What happens if people are unable to come to a consensus (or a group blocks consensus)? – Ted

Thanks so much for the question Ted! This is an important question that gets to the heart of what is unique about anarchy. There’s a lot to unpack there, so I’m going to answer it in multiple posts, starting with decision-making.

Well, what’s wrong with the current system?

I’m sure many people could give a list of things that are wrong with the current US political system: lobbying rules, money in politics, corporate personhood, widening political divide, corrupt media, obstructionist republicans, and the list goes on. (For simplicity, I’m only talking about the US and only politics. Many decisions are made outside of politics, in corporate boardrooms for example, that citizens have zero say in.) Some people would say that once we fix some of these problems the political system would work again. They believe the system is fundamentally good, but currently broken.

I’m sure many people could give a list of things that are wrong with the current US political system: lobbying rules, money in politics, corporate personhood, widening political divide, corrupt media, obstructionist republicans, and the list goes on. (For simplicity, I’m only talking about the US and only politics. Many decisions are made outside of politics, in corporate boardrooms for example, that citizens have zero say in.) Some people would say that once we fix some of these problems the political system would work again. They believe the system is fundamentally good, but currently broken.

But what if the system isn’t broken? What if it is designed to work this way? In a system based on hierarchy, where some people have more power than others, aren’t corruption and political tricks the eventual outcome? In a capitalist system based on the accumulation of wealth by the few, can’t we expect that the rich will have far greater influence over politics than the poor? Even if you could fix some of these symptoms (no small task in itself), wouldn’t corporations and politicians just find new holes to exploit? (or even reopen old ones!).

“In a system where people compete for wealth and the power that comes with it, the ones who are the most ruthless in their pursuit are the ones who end up with the most of both. Thus the capitalist system encourages deceit, exploitation, and cutthroat competition, and rewards those who go to those lengths by giving them the most power and the greatest say in what goes on in society.” – CrimethInc

Instead of constantly trying to correct a system pointed in the wrong direction (“Well yes pure capitalism is awful, we just need to regulate it more”), let’s start with a new system pointed in the right direction! A system that is inherently fair, just, and ensures the most freedom for everyone! Why start with something we don’t want and then try to water it down?

Hierarchy, capitalism, and nation-states have all had a good run. Throughout human history they have been tried in many different ways. And thousands of years later they still fail catastrophically in terms of equality, justice, and freedom. How much longer do we keep trying to fix the broken system before we throw it out and try something new?

“An oppressive system cannot be reformed, it must be entirely cast aside” – Nelson Mandela

So how would decisions be made in anarchy?

The easiest and the most accurate answer is also the most frustrating: No one knows, and no one can know. Anarchy does not lay out specific processes for how society would run because deciding things beforehand is another form of control and hierarchy. Those living in an anarchist society would decide for themselves how they want to make decisions. This means the decision-making system could evolve over time to meet the needs of the community.

“Real freedom means creating the choices you choose between” – CrimethInc

I know that’s not very satisfactory. Unfortunately there is no easy answer, so let’s answer it together: In your highest vision for society, how would you want decisions to be made? Seriously think about it. It’s easy to accept or critique other systems, but it is much more engaging to try and come up with a new one from scratch.

Examples

Thankfully, some people have put forth new ideas, so you can see what an anarchist society might look like.

In the novel The Dispossessed, Ursula K. Le Guin imagines an anarchist society with very little structure: people see what needs to be done and they do it. There is a council that discusses the issues facing society, and suggests possible resolutions. However, because there is no central authority and no way to enforce any decisions, they are really only suggestions. Everyone does what they think is best, and if there are problems, they work it out with each other.

“Is it not the most brutal imposition for one set of people to make laws that another set is coerced by force to obey?” – Emma Goldman

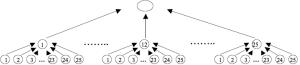

Another model I’ve heard of is called Participism. It describes cascading levels of councils where decisions are made: There’d be one for a neighborhood, then one for a city, then a larger region, and a larger region, etc. with each one making decisions for that area. However, to maintain direct democracy and local control, local councils would have the most say over what happens in their area and could veto decisions by higher councils (the opposite of current democracy, where the larger levels trump the local will).  Council members could be recalled at any time by the people they represent, and there would be very strict term limits so no one could gain too much power. This model provides a structure similar to current models of representative democracy, while addressing some of the problems with centralizing power.

Council members could be recalled at any time by the people they represent, and there would be very strict term limits so no one could gain too much power. This model provides a structure similar to current models of representative democracy, while addressing some of the problems with centralizing power.

What would you want?

I’m sure there are many more examples and many more models out there. What’s great is that all of them could be valid representations of anarchy! It depends on what we as a community want, and what works. A flexible form of decision-making would enable society to focus on what works best for the problems facing people now and in the future, instead of maintaining arbitrary laws or processes designed to address the problems of past.

Have you heard of any other societal decision making models? And more importantly, what would you want to live with? Share them in the comments or email us!

I hope this satisfied the question Ted (If not, let us know)! We’ll answer the other questions soon!